Single-lens imaging

In single-lens imaging, it surprises me how sensitive tuning the lens position becomes, the further the object is.

Of course, it’s just the simple rule of geometric optics for imaging with a single lens:

\[\frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{q} = \frac{1}{f}\]If the object is a distance $p$ away from a thin lens with focal length $f$, its image will form on the other side of the lens at a distance $q$ away. If we look at the changes of quantities for a fixed focal length we get:

\[-\frac{dp}{p^2} -\frac{dq}{q^2} =0\]For imaging a far away object, $p\rightarrow\infty$ and $q\rightarrow f$, hence

\[\frac{dq}{dp}\approx -\frac{f^2}{p^2}\]This relation tells us that if the object is much further than one f away from the lens, a tiny variation in the lens-camera distance ($dq$) results in a huge change in the position of the object, i.e. the conjugate plane of the lens ($dp$).

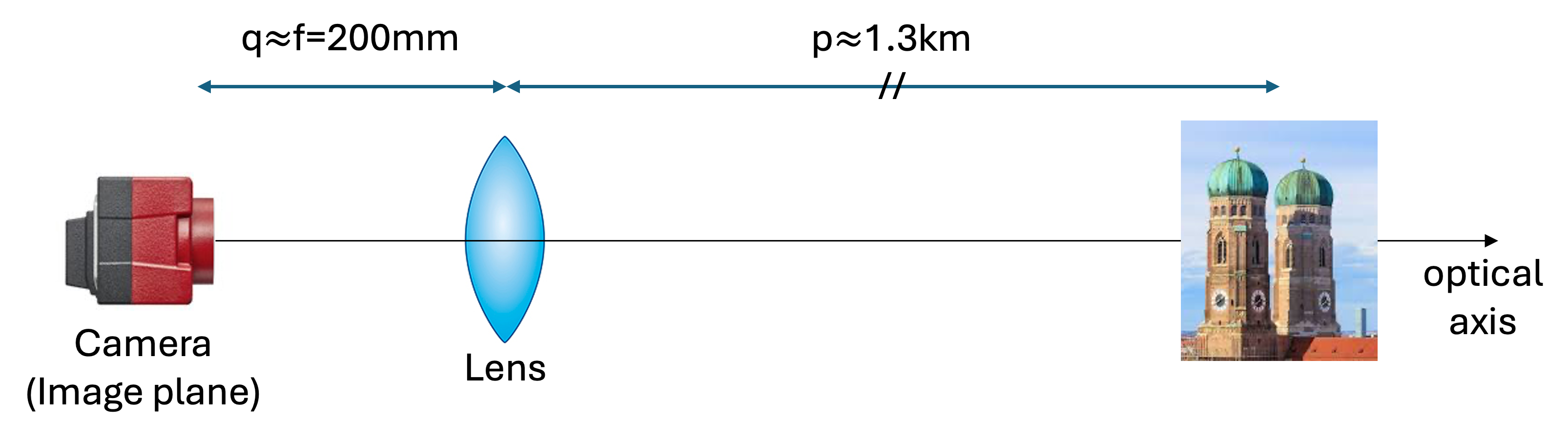

In the following video, I demonstrate imaging a building about 1300 meters away using a CMOS camera from Allied Vision and an A-coated lens with $f=200$mm.

For clarity, here’s a schematic of this simple experiment:

I first coarsly align the lens position by imaging a building nearby (about 100 meters away) and then try shooting far away. I try bringing Munich’s Frauenkirche into the focus first. Then I try to read the time from the clock on another tower nearby Frauenkirche. The lens is moved in and out to demonstrate the image getting sharp and blurry. To finely adjust the lens position, I zoom into the image frame via the camera program to see the details better.

Comments