A Glimpse Into My Nonlinear Optics Experiment

While going through some old lab photos, I found a short video from my master’s thesis experiment — just 15 seconds long, but it brought back so many memories from the lab.

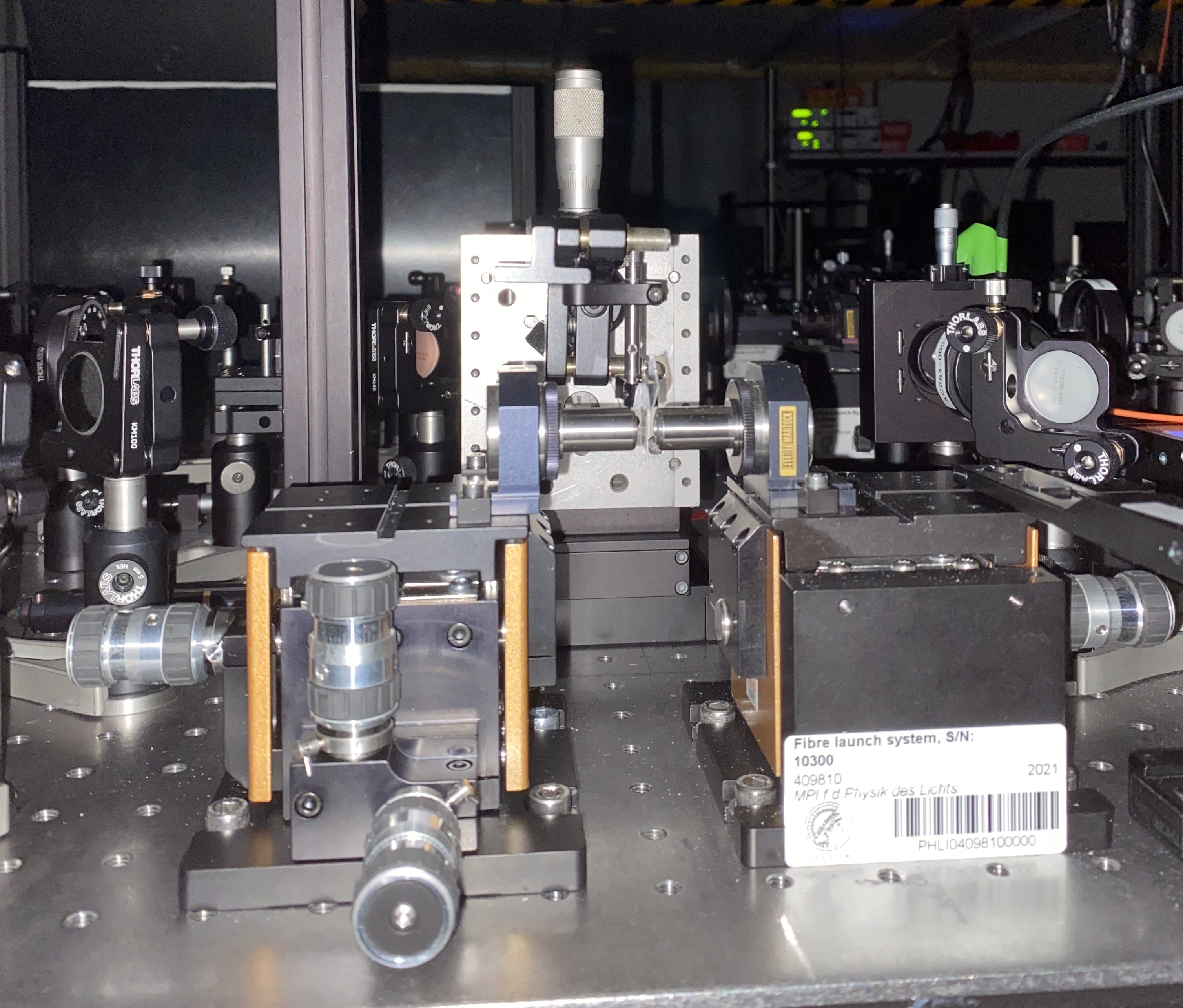

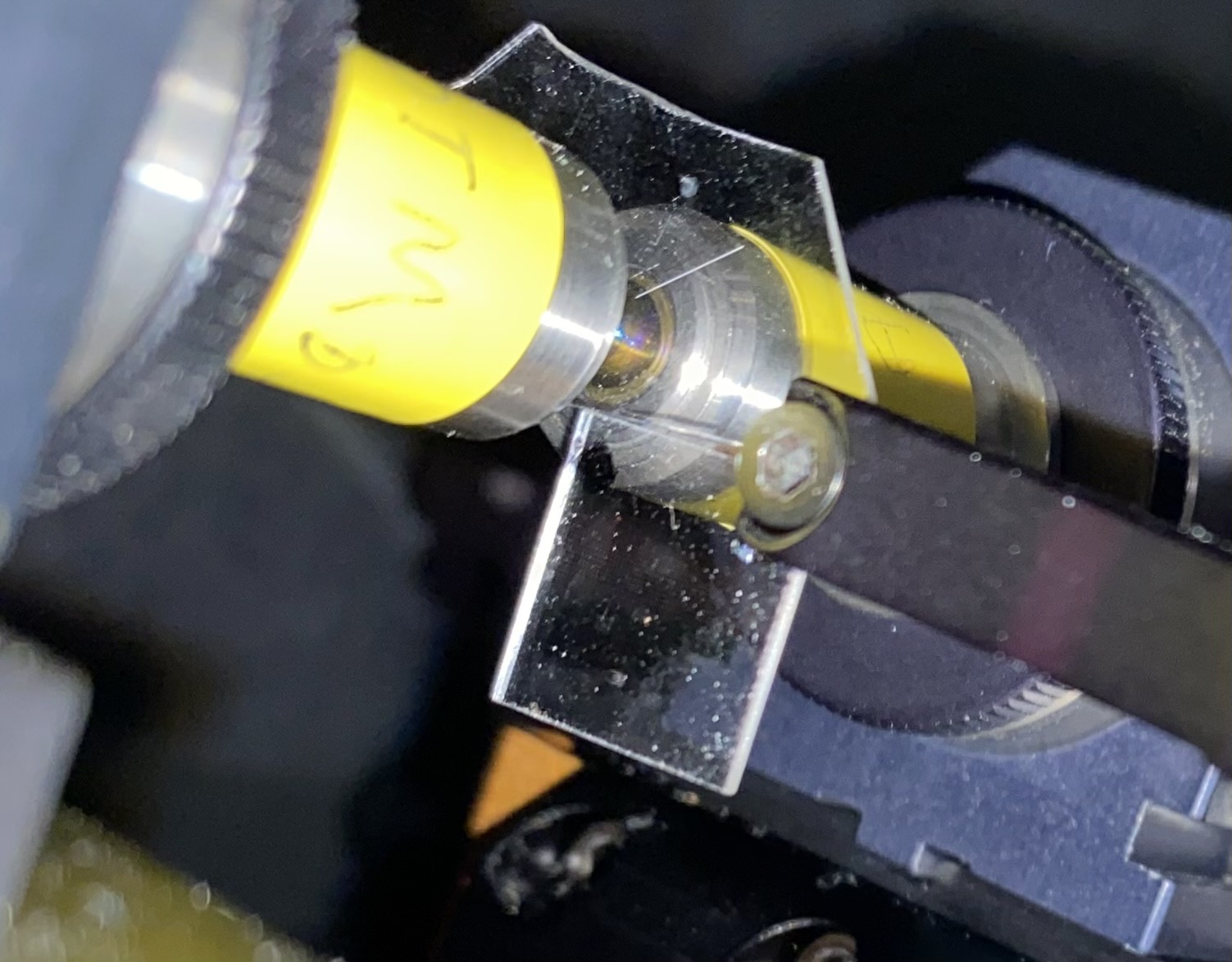

It shows a Lithium Niobate thin film mounted on an XYZ translation stage, sitting neatly between two miniature lenses (each with a 4.5 mm focal length):

During the recording, the sample is illuminated by infrared light generated through a parametric down-conversion (PDC) process in a BIBO crystal. The motivation for generating the pump light via PDC was to have an easy way to tune the wavelength over a large range. We needed this to study the wavelength dependence of the SHG process in Lithium Niobate, i.e., the dependence of its second-order nonlinear susceptibility $\chi_2$ on the pump wavelength. The BIBO crystal was pumped with a pulsed 532 nm laser, and by tuning the crystal angle — mounted on a rotation stage — we could achieve signal/idler wavelengths ranging from about 1100 nm up to around 1700 nm.

In the video, as the wavelength of the pump light changes, the Lithium Niobate glows in different colors — in the visible range. That glow comes from second-harmonic generation (SHG), where the material converts light into new colors by doubling its frequency. In this experiment, the main goal was actually to study another nonlinear crystal: Gallium Selenide (GaSe). It is possible to make very thin layers of GaSe and use them to generate entangled photon pairs via SPDC. The Gallium Selenide sample was installed side by side with the Lithium Niobate on the translation stage. Having them both on the same stage allowed for easy switching between the two samples. Because Lithium Niobate produced a stronger signal, it served as a convenient reference for calibration and verification. Here’s another picture showing both samples:

Looking back, I love how this short clip captures the magic of experimental optics — when something invisible suddenly becomes visible in a burst of color.

Comments